Geology of Madeira

The archipelago of Madeira lies on an oceanic crust aged 140 Ma (millions of years) and rises from a depth of 4.000 m on the seafloor to Pico Ruivo, the highest point at 1,862 m above sea level (on the island of Madeira). Located at the southwest tip of a volcanic chain that is mostly submerged, the archipelago extends over 700 km and encompasses the Madeira-Desertas volcanic complex (0.1 to 5 Ma), and the seamounts of Porto Santo (11-14 Ma), Seine (22 Ma), Ampere (31 Ma) and Ormonde (67 Ma). This progression of ages is the result of the movement of a classic hotspot (the emission of volcanic materials from the mantle).

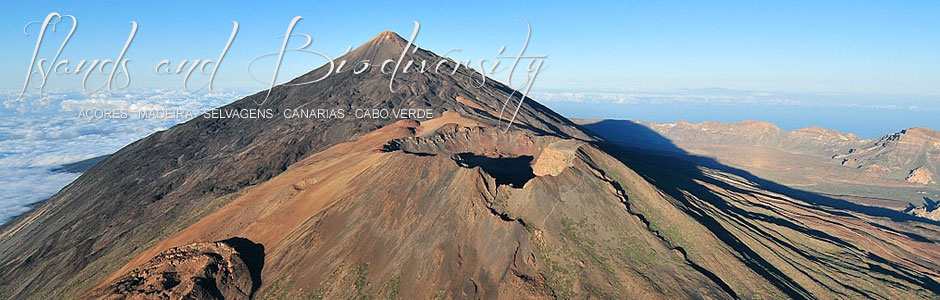

Madeira and the Desertas Islands are part of a single geological complex formed in four stages. Little is known of the first submarine stage, although it comprises roughly 95% of the total volume of materials. Submarine canyons are found on the south coast of the islands, descending from the littoral zone to 3,440 m depth, alongside fields of cinder cones and sedimentary deposits, resulting from giant landslides on the flanks of both island edifices. A second stage took place at the end of the Miocene and during the Pliocene (4.6-3.9 Ma) and corresponds to the submarine basement and oldest subaerial rocks. It consists of pyroclastic deposits and volcanic breccias, with small lava flows, locally sliced by dikes that form dense swarms in the central area of Madeira. The Desertas Islands emerged between 3.6 and 3.2 Ma, while volcanism was inactive in Madeira. The next stage occurred during the Plio-Pleistocene (3-0.7 Ma) and essentially consisted of alkaline basaltic lava flows that practically covered all the islands with a 500-metre-thick layer. The upper unit (post 0.7 Ma) consists of scoria cones and lava flows, resulting from a long period of intense erosion, mainly on the eastern flank of Madeira.

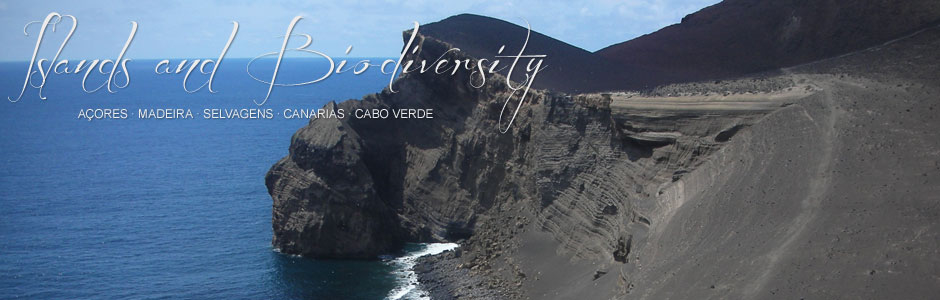

The central zone of Madeira and the Desertas is characterized by dike swarms and steep dipping, numerous faults and a great many overlapping cinder cones. These structures lie parallel to the longest axes of Madeira (E-W) and the Desertas (NNW-SSE) and are typical of volcanic rift zones, such as the Canaries and Hawaii. The landscape of Madeira is characterized by extremely rugged terrain, dominated by calderas, deep ravines and ridges. From a geological perspective, one of the archipelago’s most characteristic areas is Ponta de São Lourenço, at the northeastern tip of Madeira, whose eastern flank faces the Desertas. The paleo-relief of the peninsula shows heavy erosion, which has resulted in a geomorphology of steep south-facing slopes, while the north coast is dominated by tall sheer cliffs. Basically, it is composed of basaltic pyroclastic deposits from phreatovolcanic eruptions crossed by numerous dike swarms.

Porto Santo, which emerged during the Miocene, is located around 45 km northwest of Madeira, from which it is separated at a depth of 2000 km. The island is heavily eroded to the point that it now occupies only a third of its original surface, judging by bathymetric studies of the surrounding seabed. The northeast section of the island is composed of essentially submarine basaltic and trachytic lava flows, interspersed with levels of carbonatites deposited in shallow waters. In contrast, the western section of the island edifice was formed by a thin pile of alkaline basaltic lava flows associated with basaltic pillow lava. Both units are dissected by voluminous intrusions and basaltic and trachytic dikes, which shape most of the island’s ridges and pinnacles. On the western side of the island, the dikes are arranged in a northeast-southwest orientation, while on the eastern side they follow a radial pattern.