Geology of Cape Verde

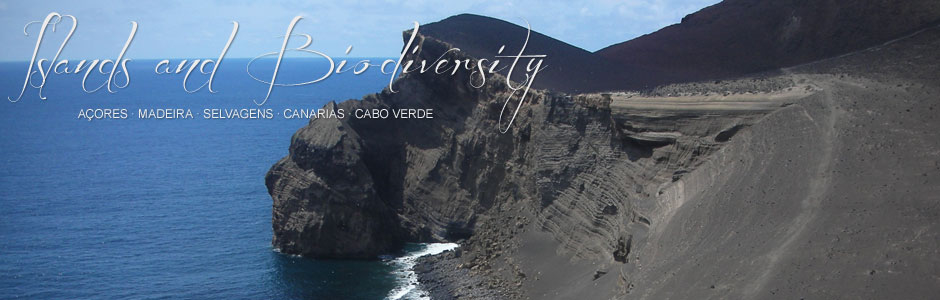

For the most part, these volcanic islands are very rugged, although the eastern islands of Sal, Boavista and Maio—which are the oldest—feature flatlands with slightly raised elevations. Nearly all the islands have well-preserved volcanic structures, such as cones, craters and calderas, and the volcanic cone of Fogo, at 2,829 m, is the highest point in the archipelago. Calderas are a common morphological feature throughout the archipelago, and a fine example is Pedra de Lume (Sal), which is hydromagmatic in origin. Sedimentary rock forms are also prevalent, such as the eolian sand deposits on Boavista. The coastline of the eastern islands is low-lying, with vast stretches of sandy beaches, whereas the Barlovento Islands have high cliffs and tiny coves.

Data on magnetic anomalies suggest that Cape Verde is located on an area of oceanic crust that dates from the Lower Cretaceous. It is believed to originate from the slow eastward movement of the African tectonic plate in relation to a hotspot with two active centres, which gave rise to the archipelago’s current west-facing open horseshoe shape. The hotspot area of action produces a topographic dome, roughly 500 km in diameter and more than 2 km above the ocean floor, known as the Cape Verde Rise. According to paleontological studies and radiometric analyses on several islands, submarine volcanic activity began in the Jurassic, although most igneous activity occurred between 25-15 Ma (millions of years), when the easternmost islands emerged (Sal, Maio, Boavista and Santiago), while the youngest (Santo Antão, São Nicolau, Brava and São Vicente) were formed during the Miocene (between 8 and 4.6 Ma), and Fogo during the Quaternary. Volcanism is currently restricted to Brava (2.9-0.24 Ma) and Fogo, where the latest eruption occurred in April 1995.

Geological studies carried out between 1976 and 1997 have established the main stratigraphic units for Cape Verde. Marine facies arranged from oldest to youngest on the ocean floor form a platform on which the archipelago is supported. These sediments are made up of clays, marls and siliceous limestones from the Upper Jurassic and Lower Cretaceous, and clays and muds from the Cenozoic, and can be observed in upwellings southwest of Maio. During the pre-Miocene, an Internal Eruptive Complex was formed; it was composed of a basaltic dike swarm of much altered granular rocks, breccia, carbonatites, phonolites and trachytes. This mixture of rocks is found in practically all the islands. Then followed what is known as the ancient marine formation, still in the pre-Miocene, which involved the deposition of layers of lava, breccia and pyroclasts. Breccia-like conglomerate formation then occurred in a terrestrial stage of lahar-like flood deposits and a marine stage of conglomerates, limestones and fossiliferous calcarenites. During the Miocene, the Principal Eruptive Complex also spanned two stages: the terrestrial, when a sequence of thick basaltic layers associated with levels of pyroclasts, phonolites, trachytes and similar rocks was laid down; and the marine, composed essentially of conglomerates, fossiliferous calcarenites and basaltic lava flows. This complex was followed by a purely terrestrial stage of Pliocene basaltic layers and pyroclasts. The end of the stratigraphic sequence is marked by the appearance of Pleistocene cinder cone, resulting from cones and small lava flows, in addition to fossil dunes and several levels of raised beaches—Pleistocene sedimentary formations—composed of alluvium deposits, debris and dunes.